I hope you enjoy reading this blog post.

James Breese, Cricket Matters FounderIf you need my help with cricket coaching, strength and conditioning, injury rehab, or nutrition, click here.

This blog shares our personal thoughts and insights into the hotly debated topic of the 2km Time Trial as a measure of cricketing fitness.

We try to dissect its validity and effectiveness for accurately gauging a cricketer’s athletic performance.

Table of Contents

The 2km time trial run has been a standard measure of fitness in cricket for years.

But as the sport continues to evolve and players are expected to be multi-dimensional athletes, it’s worth asking the question: is this test truly a fair reflection of a player’s fitness for the game?

I’ll dive into some of the requirements of cricket, analyze the 2km time trial for both men and women, and evaluate its effectiveness as a tool for measuring the fitness of cricketers, both professional and amateur alike.

Whether you’re a player, coach, or just a fan of the sport, this is a topic that’s sure to spark debate and provide valuable insight, and hopefully provide an alternative view into the state of fitness in cricket and the future of where the sport is going.

The Dane Van Niekerk Saga

Embed from Getty ImagesIn January 2023, Dane Van Niekerk, captain of South African Women’s cricket and one of their most iconic players was dropped from the team and denied the ability to feature at a home World Cup because she over-ran her two-kilometre time trial by 18 seconds, which was a personal best for her but not good enough for the standard South African cricket has set.

This made global cricketing news and sparked a media outcry with two divisive camps; one claiming it was the right thing to do, and the other outraged at the thought this could happen.

The South African cricket board require their female players to complete the distance in 9 minutes and 30 seconds (a minute more than the male players’ requirement), and 30 seconds faster than the previous standard of 10:00, which was only a guide and not a strict criterion which could cost players their places in squads.

Putting aside both sides of the argument right now, in my opinion, there’s a far bigger issue at play and that is there’s a clear lack of understanding of the purpose of the 2km time trial and its correct application.

This has become extremely evident in the past few days listening to commentators, players and the amateurs of the game discuss both its merits and its cons.

That issue is education.

The need for better education in health and fitness for cricketers runs far deeper than just a 2km time trial.

But let’s first deal with the elephant in the room, what would I do?

Should she or shouldn’t she be included in the squad?

I believe she should have been picked, based on the information that we know in the media:

- She’s still one of South Africa’s best players.

- She’s been recovering from a lower back injury and a broken ankle.

- She lost over 10kg in 6 months, which is remarkable and should be applauded.

- She passed all other testing criteria.

- I’d argue that there are no equally skilled players in the squad that could take her place, and cricket is first and foremost a game of skill. Skill comes first.

- She’s just run a personal best in the 2km. She’s ‘technically’ fitter than ever before.

- At the current point in time, you do have to make allowances in the women’s game with where it’s at.

- She’s an incredible role model for so many young aspiring female cricketers who are already struggling with an unhealthy relationship with health and fitness.

Now, there’s a big caveat to this.

If this had been a player in any of the men’s international teams, I would have agreed they should have been excluded from the squad.

Why?

Because international men’s cricket has had a lot longer to develop into the professional game, and they have a far greater pool of equally skilled talent to pick from than in the women’s game.

Take two equally skilled players, the fitter, faster, stronger, and the more agile athlete will always win.

More on that later, but you must remember the women’s game is still in its infancy professionally, and it is completely unfair to compare them both on fitness tests right now.

The media and growth of the game are also far different to what it was 30 years ago.

The rate the women’s game is developing is both inspirational and alarming as they’re having to learn to cope with things that have taken 30 years plus for the men’s game to adapt to.

They’re being asked to adhere to the same standards with no time for adaptation or change, and that’s completely unfair, particularly when it comes to health and fitness.

The human body is still the human body, it’s not like Netflix where you can get anything you want on demand. It still takes 9 months to have a baby.

Physiological and biological changes take time. It’s not going to happen overnight.

But let’s put things into perspective here and re-wind 30 years.

Can you imagine David Boon, Mike Gatting or Inzamam Ul Haq running an 8-minute 30-second 2km time trial in the early 90s?

We’d be calling for a defibrillator.

Professionalism has changed dramatically in the men’s game, the intensity the game is played at now means you cannot carry an unfit player on the team.

The women’s game is only just starting to go through that process.

10 years from now, I doubt we’ll be talking about 9-minute 30-second 2km time trials for women and that standard will be closer to 8 minutes 30 seconds.

But back to Dane Van Niekerk.

The real problem here is that she should never have been put in this situation in the first place, she should never have been asked to do the 2km time trial, and that’s on cricket South Africa’s head.

Let me explain further.

The 2km Time Trial is an Elite Fitness Test That’s Not Suitable for Everyone.

Once you achieve both the mobility and strength standards, then we can look at exercise selection through the eyes of the squat continuum:

On the surface of things, you may think that a 2km time trial run is easier than a 5km or 10km run.

The reality is, it is brutal, and the fitter and stronger you get, the harder it becomes.

This test should strike fear into the hearts of most people who’ve attempted it, and it makes every inch of their body shudder each time they perform it.

In terms of testing for cricketers, is it a perfect test? No. Is it a true test of aerobic capacity? No.

But does it give a brief snapshot into the cardiovascular capacity of a cricketer? Yes.

And is it easy to administer as part of a group and not take up half the day? Yes.

These are all things you must take into consideration when developing and administering these tests. Strength and conditioning experts and coaches are time-crunched, over worked, and don’t have much time on their hands at the best of times, whilst being paid incredibly poorly, let’s just remember that.

These are all important things to factor in here to see the bigger picture.

Now, the 2km time trial test is both physical and psychological.

It tests elements of strength and cardio, making it a great gauge of your holistic fitness. The test does this so well because you can’t cheat.

The only way to gain an advantage is by pushing harder. The clock is unbiased and unforgiving.

As the popularity of the 2km time trial has increased over the years, so has the desire to learn how to improve these times.

Thousands of people every month flock to google to learn the secrets of improving their 2km time for cricket. The problem is, they’re focusing on the wrong outcomes.

The 2km time trial will not make you a better cricketer. Running a faster 2km time trial every day, will not make you a fitter, stronger cricketer. There’s much more to it than that.

There’s an art and a science to it.

The questions we should be asking are not “how fast someone’s 2km time is” but “how fast can they run the 2km run and recover from doing it”.

Can You Do It Again?

This is important.

You will read a lot of 2km time trial articles showing you how to improve your time in a matter of weeks.

This is not that.

This article is aimed at cricketers who want to become better cricketers, not just better 2km time trial specialists.

Will it help you get faster? Absolutely.

But this doesn’t apply to Olympians or track athletes who dedicate their lives to one goal or movement.

Those folks train to give their absolute all on the competition floor.

For us mere cricketers, overall recovery should be our primary focus.

This doesn’t mean we train at the expense of athletic performance. No sirree, we’re all about that too.

For a cricketer, health, wellness, recovery, and performance go together until that pivotal tipping point into elite fitness is reached.

Though, to be honest, most cricketers will never reach that level. There’s no need.

Can you imagine running a sub-5-minute 2km? Because that’s elite level.

This is all about looking to break the seven or eight-minute barrier and not die at the end of it, and recover fast on the field, or between one game to the next.

The one significant shift to my training philosophy over the past few years, and to those of the athletes I train, has been this: How quickly can someone recover from something and do it again?

For so long, I focused on absolutes. What is my max deadlift? Max bench press? How fast can I run 2km?

I was so fixated on one individual score that I was missing out on the bigger picture of recovery.

It’s not just about how well someone can complete a task once but how well their body can recover from that task and do it again. T

his is especially important in cricket.

Just think about running multiple threes in cricket and being forced to recover fast enough to think clearly and be ready for that next ball.

For your 2km time trial, I want you to start thinking in terms of “battery performance.”

This means if I was to ask you to perform a 2km time trial, rest a short period, and then do it again, what would your second time look like?

I can tell you now, for many people, it would be awful, and they’d feel awful too.

Most cricketers think that improving their 2km time trial will significantly impact their overall cardiovascular fitness, but that is often not the case.

It may help but the issue here is a great misunderstanding of the energy systems used by the body during the 2km all-out effort.

Because it is a relatively short event (normally lasting less than 10 minutes), people assume the 2km is an anaerobic event, meaning they’re only using the anaerobic energy system without the presence of oxygen to create energy.

However, that is simply not the case.

A 2km time trial uses both anaerobic and aerobic energy, predominantly aerobic.

Modern research shows that in a 2km time trial, about 83 percent of the energy used is aerobic in nature and 17 percent anaerobic.

The goal of all energy systems is to produce the adenosine triphosphate molecule (ATP). Breaking ATP down releases energy.

The body stores limited ATP readily available for the muscular system, so energy systems are constantly at work to generate more ATP and have more energy available.

The alactic system powers high-intensity outputs from zero to 10 seconds.

The Lactic system contributes up to two to three minutes of high-intensity output in highly trained athletes.

The aerobic system fuels most of the output beyond three minutes

An important thing to note is that energy systems are not binary, as in 100 percent aerobic or 100 percent anaerobic.

Energy systems operate simultaneously, and the degree to which each contributes to output depends on the duration/intensity trade-off.

We might be tempted to think that the key to running a faster 2km is to run harder.

Let’s get the greatest intensity out of our energy system and go anaerobic as quickly as possible for as much of the race as possible.

Anyone who has tried a “fly-and-die” 2km time trial test knows that it’s not this simple.

A highly trained anaerobic system can get you through two to three minutes of high intensity output.

It is impossible to run 2km in under three minutes, so the duration of a 2km time trial means that it is always going to be majority aerobic.

Also, the downside of the anaerobic system is high fatigue.

Hypothetically, if we could race 2km at anaerobic intensity, the fatigue would become unbearably painful.

The goal of energy system performance in a 2km time trial is to get maximal aerobic power for most of the test, sparing the anaerobic system as much as possible for the final phase of the race.

At the sprint finish, we want maximal anaerobic power for the highest intensity and longest duration possible, “emptying the tank” at the end of the race.

It is an over-simplified approach to look at the energy system breakdown during this test and declare that 2km is dominantly aerobic so only aerobic training is important for success.

It is critically important to get all the energy you can out of each of your three energy systems.

Additionally, despite its relatively minimal contributions to the 2km time trial compared to the aerobic system, anaerobic system performance is significantly correlated to 2km time trial performance.

It’s a bit more complex than lacing up your runners and hoping for the best, right?

To truly pass the 2km time trial and do it well, both aerobic and anaerobic systems need to be working together in harmony.

One of the main reasons why I see so many cricketers struggle with this test is that they simply do not have the aerobic capacity to perform it and perform it well, or the ability to repeatedly perform it.

They don’t have an aerobic battery, which is a huge gap in their training.

This is why Dane Van Niekerk should never have been asked to perform this test.

She was not fit enough, strong enough or resilient enough (injuries) in the first place to attempt this type of test.

In my professional opinion they were asking her to work towards a skill set of cardiovascular capacity she wasn’t ready for.

This is a classic case of not looking at an individual approach to fitness and trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

Something, that I also understand is hard to do when dealing with multiple athletes.

The damage this has now done to her physically and mentally is profound, not to mention the wider women’s game.

It was uncalled for.

The women’s game is not ready for this form of elitism yet.

However, it will be, much sooner than you think and please do not for a second discount a need for setting a high bar in elite training standards.

High-performance cultures, require high-performance standards and benchmarks.

This is a unique case.

A Different Approach to Running a Faster 2km Time Trial

I would encourage you to consider shifting your mindset from thinking about it as a single all-out test to thinking about it as two tests back-to-back, and please do not hit me with a cricket bat at the thought of doing back-to-back 2km time trials.

Why?

Because the results of this type of test allow us to gain a far deeper understanding of your anaerobic lactic endurance ability, your aerobic ability, and the body’s overall ability to recover (your aerobic battery).

This is extremely important in terms of athletic performance for cricket and the health of the cricketer.

Just think of the impact it would have on your performance if you’re able to recover faster: You’d have more energy and could make better decisions at the crease and on the field leading to better performance.

The 2km time trial, as I mentioned above, is roughly 17 percent anaerobic and 83 percent aerobic in nature.

It’s important to understand the role of lactic acid, which is so often seen as the cause of poor cardiovascular capacity.

Lactic acid only appears in the body when the body can no longer work aerobically and anaerobic glycolysis occurs.

There are two golden rules of developing the cardiovascular system:

- Reduce the production of lactate by having a higher aerobic threshold.

- Increase the rate of lactate removal from the working muscles by having a fully functioning anaerobic system.

Step 1 is all about maximizing your aerobic threshold.

Step 2 is about maximizing your anaerobic threshold.

Both need to be trained very differently, but both are key to maximizing the cardiovascular system.

From a cardiovascular endurance performance standpoint, the ability to make use of lactate in the muscles as fuel is one of the most important training adaptations you can make as an athlete.

This is why having a strong, robust anaerobic system is important to maximizing your cardiovascular potential.

Once you have maximized your aerobic threshold, which focuses on reducing the rate at which lactate is produced, you can then focus on improving the body’s ability to remove it.

The best way to view your cardiovascular system is to think of it as a vacuum, which sucks up all the lactate.

The greater the aerobic threshold, the bigger the vacuum.

The bigger the capacity of the vacuum, the more the anaerobic system can contribute to the overall energy production within the body.

The greater the aerobic threshold, the bigger the vacuum.

The more robust and trained the anaerobic system is, the MORE powerful the vacuum becomes, thus sucking up lactate at a much faster rate, allowing you to perform faster and for longer.

This is why you can never fully maximize your cardiovascular potential, no matter how high the intensity of the exercise you do, if you don’t fully develop your aerobic threshold first.

Your vacuum simply isn’t big enough to hold all the lactate the body produces.

It’s like trying to put a V8 engine inside a smart car.

The key to maximal cardiovascular development is combining both aerobic threshold development and anaerobic threshold development.

Going back to Dane Van Niekerk, and countless other cricketers out there who are struggling with the 2km time trial, it’s highly probable that she has poor aerobic capacity.

And it’s not faster 2km runs and tests she should be doing.

It’s longer, slower aerobic pieces first, to then earn the right to go faster later, so she can recover faster.

So, what would be a more appropriate way of testing people in a similar position, well I think we need to look at the order of the tests, and give people stepping stones and benchmarks to reach before even touching the 2km time trial.

Something I think could benefit not just the pros, but club cricketers all over the world too.

The Cricket Matters Cardiovascular Training System

When developing the cardiovascular system, in my humble opinion, it’s all about expanding the comfort zone.

Why?

Because it’s so damn hard and it sucks if you go too hard, too fast, too soon.

It takes time, patience, and commitment, which are all things society struggles with.

If we don’t find something easy, we tend to give up.

I want cricketers to stick with it because cardio training can be an enjoyable process if done correctly, I promise.

So here are the testing standards I would work through when working with a cricket athlete, irrespective of ability in terms of building up their aerobic battery:

- 20-minute walk test. Can you walk 1.5 miles (2.41km) in 20 minutes? Yes/No

- Can you run 5km in under 27:30 for women, and 24:30 for men? Yes/No

- Can you run 10km in under 55 minutes for women, and 48 minutes for men? Yes/No

- Can you run 2km in under 9:30 for women, and 8:30 for women? Yes/No

- Can you run a 400m x 2 test, resting 90 seconds between efforts with a combined time of less than 2 minutes 20 seconds for men, and 2 minutes 50 seconds for women? And, is your second time less than 10% greater than your first effort? Yes/No

Points 1 – 3 are not elite by any stretch of the imagination, but they start off as stepping stones that lead to the next process.

You keep going in order until you can hit the required times.

The 2km time trial is fourth on our list, with the final test for ultimate performance being the 400m x 2 to test how good a cricketer’s aerobic battery is.

This type of testing has been around for decades in other high-end sports, and I’ve drawn a lot of influence from the highest levels of CrossFit.

Not that I think cricketers should do CrossFit in the slightest, but we can learn a thing or two at the elite levels on how fast they can recover.

For the 400m x 2, the athlete should pace accordingly so that they don’t die in the first 400 meters and merely survive the second.

The intent should be coached, as the point is to do the best possible total 800m when the two 400 meters are added together.

With the timeframe being one minute and 5 seconds to one minute and 30 seconds per effort, the test analyzes repeatability in a pure cyclical muscle endurance sense.

More specifically, the test gives insight into four areas: lactic endurance ability, repeatability, aerobic ability and recovery.

The second score should be as close as possible to this or at most, 10% longer. That is 110% of the first score for 400 meters.

If the athlete scored the same in both sets, that would indicate a need in training for both increased lactic endurance and recovery.

Having the second score over 10%, would indicate a need in training for an aerobic system to work in line with their high-power lactate ability.

Having scores a solid percentage apart from one another, but absolute scores being poor, for example an elite male with a 1:20 and a 1:30 score would require improvement of all areas, including volume, metabolic skill, increase in aerobic potential, increase in strength etc.

Scores that are lower on the second 400 meters meanwhile, for example, an elite male running at 1:12 seconds and then 1:06 would indicate CNS fatigue, an overreached state, a highly dampened person, a poor warmup prior to the test, or simply just an older training age that requires a higher level of stress in order to stimulate the metabolic system for that specific test.

Now, I want to make perfectly clear one thing.

I’m basing the numbers above based on other elite sports.

I do not think that the 400m x 2 test has ever been tested in elite cricket, but I would suggest doing further research on cricketers who can successfully pass all other tests and get some compelling data to progress this idea forward.

After all, there’s a strong element of power endurance in cricket, and I feel this test, at the highest levels would be appropriate.

Cricketers need that ability to recover quickly because it’s all about decision making on the field.

A poor aerobic base leads to poorer decisions on the field, it’s why the 2km time trial exists in the first place.

It’s why I test and take cricketers through that 5-step process above.

Don’t discount the walk test and skip it, it’s harder than you think, and certainly don’t go anywhere near the 400m x 2 test until you’re fit enough and strong enough to even reach the entry standards for the first of the two 400m.

Final Thoughts: 2km Time Trial for Cricketers

I do believe that the 2km time trial is a fair measure of cricket fitness at the highest levels.

I would go so far as to suggest to progress it further by adding a 400m x 2 test.

However, cricketers need to earn the right to get there first by going through our 5-step process.

I certainly would not get the average club cricketer doing these tests up and down the country straight away, and certainly not the over-50s Welsh team I work with.

Increased cardiovascular capacity leads to improved mental acuity.

With all my experience working in elite police and military units, it’s what separates the very best from the rest, it’s not just about having good skills, but the ability to do them under pressure and under duress.

Cricket has so much in common with the military and police worlds, it’s uncanny.

Cricket is all about decision making, and to make better decisions and think clearly under pressure we need a strong, robust cardiovascular system.

Something you don’t get from just doing 10 – 15 seconds of shuttles for 10 minutes.

It’s about having the mental clarity to know when to leave the ball, when to play the ball, what ball to bowl under pressure etc. etc.

Some of the comments I’ve heard on the radio and commentary suggest cricketers don’t need to do this test.

This to me shows a lack of understanding as to why it’s being performed in the first place, and maybe the cricketing governing bodies need to take responsibility for this to better educate their players and the wider audience.

A strong robust cardiovascular system developed well will lead to better performance on the field.

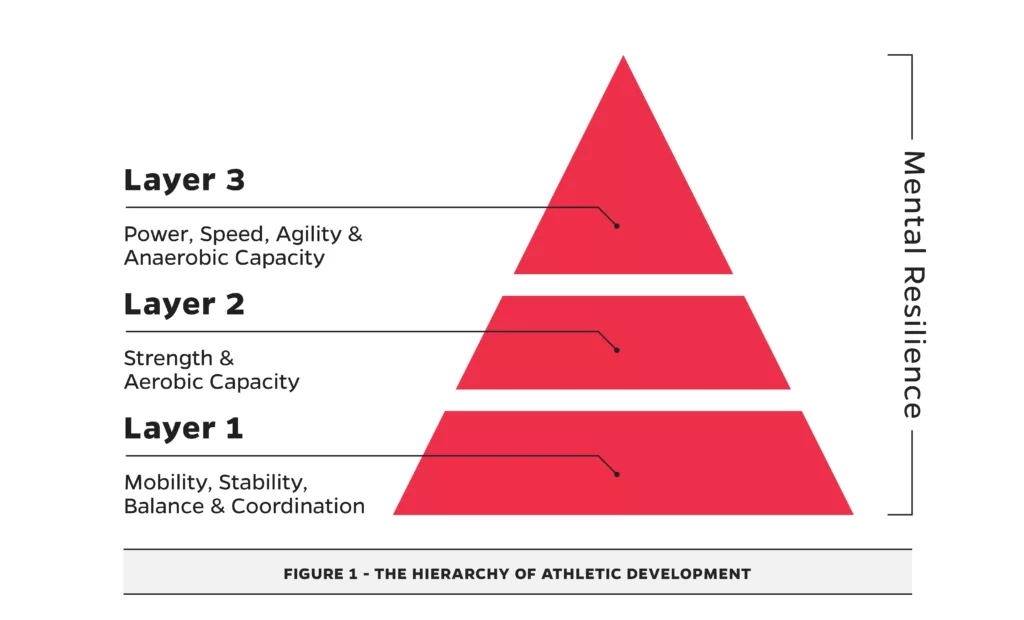

But it’s not a test you should jump straight to. In the Cricket Matters training system, it’s what we call a Layer 3 test.

If there’s one thing I ask you to take away from this approach is that your ability to recover faster and repeat the work is far more important to overall health and performance than the actual times.

And this carries over to other aspects of training when you apply the Cricket Matters System.

Enjoy the challenge, and please don’t hit me with a bat next time you see me having performed the 2km time trial and the 400m x 2 test.

Further Reading

FAQs

What is the 2km Time Trial in Cricket?

The 2km time trial is a fitness test used in cricket to assess an athlete’s endurance and cardiovascular fitness. Cricketers are required to run 2 kilometers as fast as possible, with their time recorded as a measure of fitness.

How Does the 2km Time Trial Measure a Cricketer’s Fitness?

This trial measures a cricketer’s cardiovascular endurance, stamina, and speed. A faster time indicates a higher level of fitness, reflecting the player’s ability to sustain energy throughout a game

Why was Dane Van Niekerk, South African Women’s Cricket Captain, Dropped from the Team?

Dane Van Niekerk was dropped from the South African team for not meeting the specific fitness standard of completing a 2km run in 9 minutes and 30 seconds. Despite achieving a personal best, Van Niekerk’s time was 18 seconds over the required limit, as reported by ESPN Cricinfo.

How Do I Train for a 2km Time Trial in Cricket?

Training for a 2km time trial involves a combination of endurance and speed workouts. Begin with regular long-distance running to build stamina. Incorporate interval training, like sprints, to improve speed and aerobic capacity. Gradually increase the intensity and frequency of your workouts for continuous improvement.

![[Case Study] Advanced Hiit Training Plan for Cricketers 5 Hiit Training for Cricketers](https://www.cricketmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/HIIT_Training-1024x536.png)